On Loss and Overcoming Obstacles

This evening, when the sun began to set and the temperature dipped below 100 degrees, I decided to take a break from sitting in front of the fan and mustered my energy to step outside for a run. I figured that with the increasingly sedentary lifestyle I was beginning to acquire as a result of the soaring temperatures, a bit of physical activity would probably do me good. Besides, I was already dripping in sweat so profusely, that a run would hardly change anything.

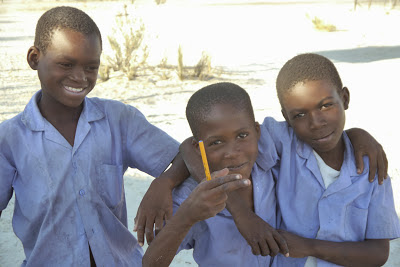

I set off down the sand tracks behind my house and decided to explore the far reaches of the village. I didn’t get far, however, before I heard distant voices yelling “Miss Erika, wait for me! Wait for me!” It was the children from a nearby homestead and they were eager to join me on my afternoon adventure.

I waited for them to catch up to me and heard little Thomas crying “run!” as he zoomed past, ready to race. We raced a few times to various trees and homesteads and, when I could see that everyone was tired, we practiced cartwheels and handstands.

Suddenly, a well-spoken little thirteen year old boy named Embara, who I had befriended a few days earlier while tossing a Frisbee, looked at me and asked “can we go visit my father?”

I was a bit taken aback and I didn’t quite know what to say, so I answered “why not? Where is he?”

Embara pointed toward a nearby homestead.

“Okay, let’s race there” I said.

The five primary school learners and I sprinted in the direction of the homestead. Yet, before I reached it, I heard Embara shout

“no Miss! This way!”

I changed courses and followed Embara on a path to the left of the homestead. I was expecting him to lead me to a house but, instead, he directed me straight to a cemetery that I never knew existed.

He walked to his father’s grave and pointed to the tombstone. Embara’s father had died this past summer and left him an orphan.

My heart sank. I was at a loss for words. All I could say was “I’m so sorry to hear

that.”

The children all led me around the cemetery. They pointed out the graves of their aunts, uncles, grandparents and neighbors. Many of the tombstones contained the surnames of my learners and I could only guess that they were the names of their deceased

parents and relatives.

I don’t know why hearing about the loss of these children came at such a surprise to me, or why it affected me so deeply. I know that Embara’s experience is not unique. I know full well that many of the children I teach every day are orphans and vulnerable children. I know that nearly half have been raised in child-headed households or by single grandmothers.

Earlier this term, when I was grading papers in the main office building at night, I was made fully aware of the severity of Namibia’s “orphan crisis.” I had walked into the counselor’s office to borrow a pair of scissors and, laying on her desk, I saw a file labeled “OVC register”—a registry of orphans and vulnerable children.

Out of curiosity, I flipped through the pages. What I witnessed hit me like a punch in the face.

Perhaps it is putting these experiences to the names and faces of learners I see every day, but it never ceases to break my heart when I find out that yet another one of my learners has experienced the trauma of losing a close family member.

When I scanned the list of my grade 8 students on the register, I saw that over half of them lost at least one parent. Many of them lost both.

I thought back to my own life and to how very little I really know about loss. My brain was swimming for answers and explanations. I was supposed to be the teacher, but I really had no valuable information to impart on my learners. I really do not understand

the meaning of loss–at least not to the extent that these children do.

As I stood next to Embara’s father’s grave, I tried to give the children comforting words, but I’m sure I offered little more than an incoherent jumble.

Finally, I was able to string together a sentence and asked “can we bring him flowers? Maybe

we can find some pretty leaves to decorate the tombstone?”

The children all laughed. Apparently I had made the silly mistake of forgetting that the goats and cows would eat all the living

plants.

The plastic flowers that had been carried away from other tombstones by the wind and by hungry goats would have to do.

We spent the next few minutes in silence, gathering the remnants of plastic flowers that littered the area and positioning them

neatly on his father’s grave. Finally, Embara said somberly “We are having a problem. Too much people die here.”

I nodded. What could I say?

HIV/AIDS is a leading cause of death in Namibia. Yet, common “western” illnesses like cancer, heart disease and diabetes are also

taking their toll. Ill health and road deaths have combined to deplete much of middle-aged population in the country and, as a result, working-age people are few and far between. It is their children that must somehow rise to the occasion and pull themselves up from the straps of their tattered shoes. They must find the intrinsic motivation to continue their studies and seek out opportunities.

Unfortunately, this is something that I am not qualified to teach them. I have never been in their shoes. I don’t really know

what they are going through and, as much as I try to convince them that learning to write sentences in the passive voice is an essential skill in their lives, I know that it is not.

I can do my best, but I know that for most children my words of encouragement will not be enough.

Yet, children like Embara give me hope for the next generation. He is an orphan, raised by distant family members in a corrugated metal shack. But he is bright, motivated and eager to learn. Embara proudly proclaimed that he had finished term two with the second highest marks in his grade five class. He is curious and inquisitive and his English rivals that of many of my eighth graders. He might not have people to push him, but he somehow found that inner drive within himself.

And while I failed to give Embara the encouragement I was hoping to provide during our evening run, I’m pretty sure he somehow inadvertently reciprocated the favor.

I have recently been experiencing one of the low-points in my service—frustrated by the intermittent internet access in the computer lab, the promised funding for my school mural that recently fell through, the chaos of grade ten exams and end-of-year-itis that I am beginning to see in many of my learners. Embara reminded me that I need to finish strong.

He shed light on the trivial nature of the obstacles standing in the way of my success and once again reminded me to keep looking

forward.

I spent all year trying to teach my learners the importance of motivation and overcoming challenges, and yet my learners already know how to win these battles.

While I fumbled and stumbled, trying to muster up an explanation on the importance of staying strong and moving on, I didn’t realize that these were precisely the most important lessons that my learners have so effortlessly been teaching me.